The Pleasure* Of... Learning

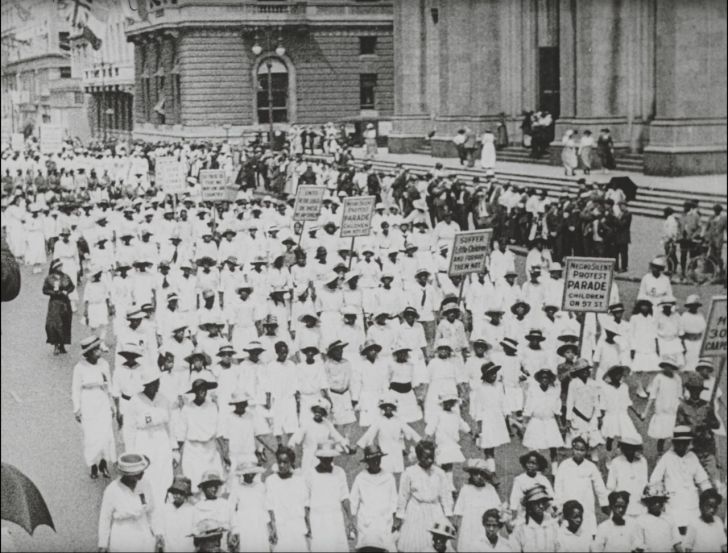

Taking to the streets against racist violence, 103 years ago. And again, in spirit.

*“Pleasure” has always been a rough approximation for what I’m trying to explore in this space, which covers something more like joy, happiness, rootedness, and connectedness, and the ephemeral sensory and cultural experiences that are far more powerful, and vital, in generating them than we often think. But that’s less snappy. Also, the slightly debased, cheap and cheerful associations of pleasure usually work for me, even if what I’m discussing is not obviously pleasurable.

But not this week. This week, there’s only fury and energy and purpose. For white women like me, for white parents, there’s listening and learning. Taking part where we can, donating, and sharing what we can.

Here’s a little bit of what I know about the history of protest against racist violence in America. In 2017, when my colleagues and I put together the “Hotbed” exhibition at the New-York Historical Society, we were trying to illustrate the way that different strands of progressive activism came together in a unique concentration in Greenwich Village, in the early decades of the 20th century. The exhibition marked the centennial of women’s suffrage in the state, but what interested us were the overlaps between voting rights and other movements. The same people showing up to fight for the rights of workers and women, and against war and lynching. (My book is about the same subject, specifically the women in those fights.)

There were plenty of caveats to this intersectional version of history, and the biggest was around race. On the one hand, the NAACP was headquartered just north of the Village and its founders, most of whom were white and Jewish, were active in related causes as well; white activists contributed to The Crisis and black writers to white progressive publications—occasionally. We featured a fascinating white English feminist, Elisabeth Freeman, who used a suffrage speaking tour to the American South as cover for gathering information for the NAACP about a lynching in Nashville. Her foreignness perhaps enabled her to speak out more freely against racist violence in the US than was possible or palatable for American women; and her whiteness undoubtedly protected her as she did so.

On the other hand, most of the activists we featured in the show accepted as a basic truth that there was a thick, uncrossable line between black and white America, and that people’s experiences and expectations of life were fundamentally different on each side of that line. Even in their progressive sympathy for the injustices African Americans were suffering under Jim Crow, they could not quite reach empathy.

Our focus was also on techniques of protest, how different movements learned from each other. Young women left their factory benches and draped themselves in sashes to commemorate their fellow workers killed in the Triangle fire; suffragists learned that getting shoved and attacked by male onlookers while the police watched (or joined in) could shock neutral observers into support. Everyone learned the power of numbers, pageantry, and press attention.

In 1917, the NAACP organized its first march in New York to protest ongoing violence against black Americans—what are sometimes still called “race riots” but are more accurately described as campaigns of terror, pogroms or massacres. The specific occasion was a killing spree in East St. Louis, Illinois, after black workers were brought in to replace striking white laborers at a local factory. Spurred on by the rumor of a robbery committed by an armed black man, these furious white men unleashed a wave of terror that began on May 28–103 years ago to the day from the start of the protests over George Floyd’s murder. On July 2nd, there was a reprise, in which white mobs killed at least 100 people. (There was eventually a Congressional investigation into the events that indicted several police officers—not, in this case, for causing violence but for standing by, or running away, while it raged.)

The march up Fifth Avenue in solidarity on July 28 was carefully organized by the NAACP, who decided against a racially mixed event. An appeal went out to black New Yorkers that was framed as a sign of solidarity with, indeed an obligation to their race, who were the principle victims of the violence. Nearly ten thousand smartly dressed men, women and children lined up in separate rows, the women all in white, echoing a signifier of purity and respectability regularly deployed by the suffragists. They walked in silence, accompanied only by “muffled drums,” carrying banners said things like “Race Prejudice is the Offspring of Ignorance and the Mother of Lynching.” It was a peaceful, dignified, march, and certainly drew attention to the cause. But the violence continued. And continued. And more than a century on, here we are.

(Incidentally, we wanted to include the image of a female Black Lives Matter protestor in the closing image of the exhibition, a photomontage of historic and contemporary protest against a backdrop of the first Women’s March, meant to illustrate how overlapping causes still, well, overlap. We weren’t allowed; museum higher-ups claimed—among other things—that it might upset the hypothetical visiting child of a police officer.)

Here’s the footage, anyway. It’s quite something.

Credit to Bill Morrison, who worked with us on the exhibit, uncovered this newsreel, and used it in his excellent documentary Dawson City: Frozen Time.